Every victory means a change in the status quo

Re-reading Orwell, Shor, and the Third Way, and finding a way forward

Some weeks ago, my friend sent me an email asking if I’d read “Politics and the English Language” by George Orwell. We’d had a conversation about the importance of being specific when talking about political candidates, parties, voters, issues.

I realized I had a book that includes this essay, Why I Write, from Penguin. It includes the essay he recommended, as well as the title essay, plus a lengthy piece called “The Lion and the Unicorn”, and a short essay called “A Hanging.”

I can not recommend this book enough. Seriously, get it now.

The piece called “The Lion and the Unicorn” probably radicalized me; “A Hanging” caused me to weep. And “Politics and the English Language” is something that all the moderate Democrats who worry that their lefty colleagues use too much highfalutin’ language when talking to normies might want to take up; a few of their lefty colleagues probably should, too, but for different reasons.

The problem with the center of the party is its tendency to default to lazy metaphors, outdated turns of phrase, empty gestures of language. They wave at ideas but never grab them. They invoke imagery from 1950s domestic sit-coms. They talk about “everyday people” and “kitchen table issues”.

When politicians and pundits say these phrases, I get the distinct impression they have nothing in their heads, they’ve put their politics in self-driving mode. As Orwell put it, “The writer either has a meaning and cannot express it, or he inadvertently says something else, or he is almost indifferent as to whether his words mean anything or not.”

Other times, though, I think they are engaged in some form of dishonesty. Orwell describes one style he calls being “consciously dishonest.” He describes political speakers who “fear that they might have to stop using the word [here, democracy] if it were tied down to any one meaning… [T]he person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different.”

After finishing Why I Write — well, first I went outside to look at the early shoots of spring, trying to remember what I’d planted where, and admiring the daffodils that every spring give me reason to hope that the moles and voles didn’t destroy everything over the winter — and then I came back inside to re-read two other, far less inspirational documents.

The Summary Report from the Third Way “Comeback Retreat”

In early February, “a group of highly experienced and passionate professionals” met under the organization of Third Way on a weekend to “chart the Democratic comeback.”

If I knew how to make YouTube response videos, I’d make one about this document. There is so much in it that I suspect is consciously dishonest.

From the way that they order their list of reasons “Why Democrats Have a Cultural Disconnect with the Working Class”, and their use of passive voice and what Orwell calls “verbal false limbs” (e.g., “are seen as” — by whom?) and undefined labels (“everyday people”), to their ability to turn one point into several, repeating points, the document gives me the sense that these are not serious people.

When the document uses the phrase “are seen as”, I find myself wondering, by whom?

Still, let’s look at what Democrats “are seen as”:

“are often viewed as judgmental, out-of-touch, and dismissive”

“making them seem disconnected from everyday people”

“are seen as more focused on cultural and social issues”

“are perceived as intolerant of internal debate”

“are seen as defending elite institutions… while being critical of institutions working-class people value (churches, small businesses, police).

“making it seem like Democrats are more extreme than they actually are”

“making them seem pessimistic and unpatriotic”

“are seen as hostile to success, indifferent to people’s desire to attain wealth, while reflexively attacking wealthy business leaders”

“Voters see Democrats as favoring excessive regulations, inefficient spending, and programs that don’t directly benefit them”

“are seen as focusing on redistribution rather than wealth creation”

[a focus on climate change] “is seen as harming job opportunities and economic growth”

This is a list of attributes that “highly experienced and passionate political professionals” who, in this document, describe themselves as “progressives” assigned to their own party.

Why use these verbal false limbs? Why distance yourself from your own beliefs about your own party? And, are we sure that the group convened by Third Way is, in fact, progressive, or are we now using that term in a consciously dishonest way?

Back in 2016, when the term “progressive” was ascendant, there was a debate over who got to be progressive. Clinton and Sanders argued over it in debates. The BBC published this piece trying to offer a working definition, but their circa 2016 answer doesn’t fit what the Third Way folks have in mind:

“A progressive is someone who wants to see more economic and social equality - and hopes to see more gains in feminism and gay rights. They're also supportive of social programmes directed by the state - and they'd like social movements have more power in the US.”

The Third Way “Comeback Retreat” report is explicitly against prioritizing “gains in feminism and gay rights” and explicitly against social movements having more power. Their recommendations include “Move Away From Identity Politics” and “Reduce Far-Left Influence and Infrastructure”.

I’ll link to the report itself, but I want to offer a briefer rewrite of their recommendations for how to “Reconnect Culturally with the Working Class”.

Appeal to common values, as long as those values don’t include diversity, equity, or inclusion.

Use plain language, except when that language includes the words “billionaires”, “corporations” and “minimum wage”.

Show up where the audience is.

Don’t scold your moderate or conservative colleagues; do scold your left colleagues.

Build an exclusive clique of moderates and keep out the left.

Don’t let your donors tell you what to do.

Cater only to one specific demographic group: male voters.

There. That’s clearer. Now that we’ve cut through the muck, I can see what the strategy is here. Make nice with business; pander to the working class; listen to your consultants.

Oh, and “Conduct a comprehensive study on media consumption to better understand how to reach voters”. They need to do quite a bit more research than just a media diet study to test all their beliefs and recommendations. Want to know how I know that? They use the term “prosperity gospel” in a way that tells me they don’t know what that is. Or maybe it’s a “strategic misunderstanding”.

The Blue Rose Research Report: “2024 Retrospective and Looking Forward”

Again, if I knew how to do a YouTube response video, I’d make one about this report. There’s so much about it that offends me as a researcher and a strategist. I’ll try to give a brief overview of that before I tell you what’s really wrong with it.

It’s data-babble.

It’s written for a specific audience, and we aren’t it.

Here’s the first real problem:

This is a report that jumped the starting bell — Shor and company are trying to frame the conversation ahead of much deeper, more detailed, and more data-driven analysis of the election results in 2024. It has become conventional wisdom already in many centrist social media/streaming media channels. If you want to know what happened in 2024, below is a link to a much more robust analysis than Blue Rose gave us, working with high-quality data sets:

You can also turn to ANES, who has preliminary data-sets available for 2024 here.

Why would Shor and his team want to get out ahead of these more robust, academic analyses? It’s so that they can set the narrative. If they can establish the idea that undecided or otherwise disengaged voters (which is a euphemism for non-voters and infrequent voters), are far more conservative, they can help steer the next campaign cycle towards more centrist, pro-business policy positions, and away from The Groups.

You should always know what the agenda driving a research report is. In the commercial space — whether in political or brand marketing — we are not doing research to satisfy our curiosity (I wish!). If we’re being honest, we are trying to figure out what our options are and which one will help us reach our goal.

If we’re being dishonest, we’re trying to prove we’re right.

Here’s the second problem. So what?

Let’s grant that swing voters, and young men, and possibly naturalized citizens are more likely to vote Republican. Let’s grant that people who use TikTok became a little less likely to vote for Democrats in 2024.

What are you going to do about it?

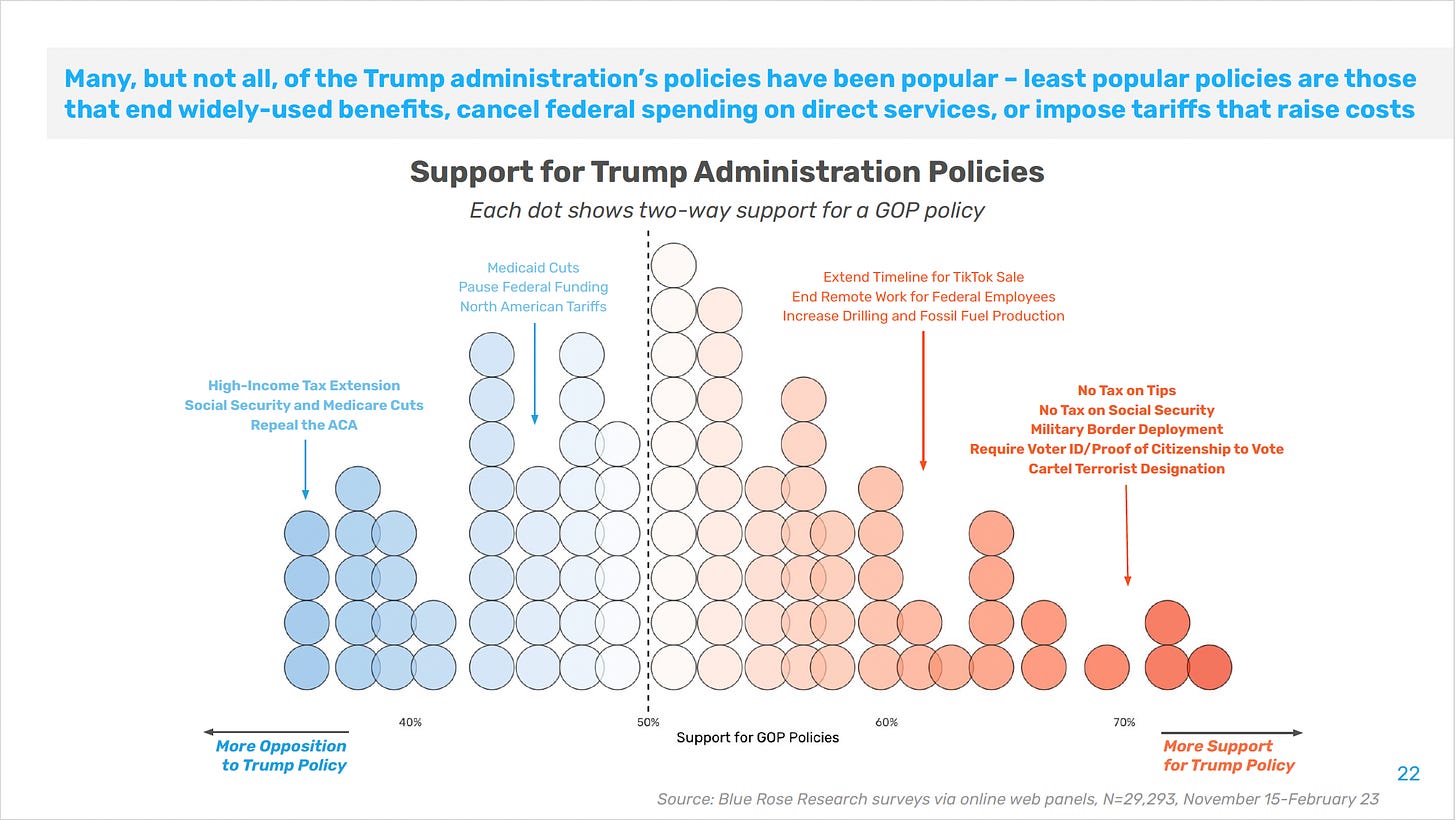

There’s a particularly interesting chart mapping out the issues that drive more opposition or more support for Trump.

If I take the issues on the wings of the chart — the ones that drive more opposition and more support1 that are also generally compatible with Democratic policies (at least as articulated by the Harris campaign), here’s what we get as a policy slate:

No tax on tips

No tax on social security benefits

End the tax cuts for high-income earners (the 2017 tax cuts)

Stop cuts to Social Security and Medicare

Stop cuts to Medicaid

Protect the ACA

Protect federal spending on direct services

Stop tariffs that increase costs

Let’s just stipulate that this is identical to Harris’ campaign platform.

If that’s the case — and it is — then why don’t people trust Democrats on these issues?

If TikTok news watchers who aren’t highly politically engaged are slipping away from Democrats, and are a key demographic to capture — what should Democrats being doing on TikTok?

What is the strategy, guys?

What Would My Clients Do?

Let’s pretend the Democratic Party is a normal brand marketing client that might come to my company. They might tell me something like:

“We are constantly fighting it out in the top-2 box of consumer preference, and lately, we’ve been falling behind our biggest competitor. We have some ideas about which customer segments we’re underperforming with, and why. Can you help us figure out where the bleeding is coming from, how to stop it, and how to grow again?”

Now this is a client that is absolutely swimming in data. They’ve got customer segmentation studies spilling out of file drawers; they’ve got a customer panel they can tap for real-time feedback; they’ve been doing a quarterly brand tracker for 40 years. But the math ain’t mathing. They’re falling behind.

When quantitative research isn’t answering your question, there is another tool in the toolkit. Talk to humans.

I’d propose a national ethnographic study first. We’d do some in person, some via digital diaries. We’d want to meet them in their own context to understand what their lifestyles are like, what their communities are like, what kind of work they do, how they live, what their family dynamics are, how they spend their time, their money and their attention. We’d want to explore their values — what they believe in, and who they believe in. What drives them, and how they see themselves. Are they where they want to be? What’s getting in their way? What would make it easier for them to get there?

But there’s a catch:

We wouldn’t ask them a single question about “politics”.

We’d learn from people how they actually talk about their lives. We’d learn about their struggles and their sources of joy, what they’re proud of and optimistic about, and what brings them a sense of shame, isolation or fear.

And we’d use what people tell us to come up with the ideas that would address their real needs and celebrate their real selves. We’d develop those ideas into something more than “messages” — a lot of times we make posters, or other “ad-like objects” (adlobs, for the nerds) that bring to life the idea we’re trying to convey.

And then we’d bring real people back into creative workshops together. They’re not there to give up-or-down votes to ideas. We’d set them up around a big room like a gallery, and let them see everything — they’d get to decide what they wanted to talk about first. And we’d let them just talk. Eventually, we’d ask some pointed questions, but we’d start with “what do you make of this?” And let them cook. We’d want to learn:

How can we make it more specific?

How can we make it more true?

How can we make it more relevant to people?

How do we make it more real, and more relatable?

We’d enlist these people, these “everyday people”, in the creative exercise of pushing these ideas into a more compelling place.

And then we’d use these ideas as a jumping-off point for making actual creative — videos, audio ads, outdoor boards. We’d just run them. See which ones get people excited — which ones get them to visit a website, download an app, make a donation, sign up to volunteer, or come to an event. The ones that demonstrably work get paid media investment. The ones that don’t work, we toss.

Or, I don’t know, maybe some we take back to the drawing board. Convene some more workshops to figure out how we fell short, try again. Run them again, see if it works better.

And we’d launch those now. Not in January, when the election kicks off in earnest. We’d be in field right now, developing concepts by the end of the summer, piloting creative online by the fall.

The measure of effectiveness would not be how many people gave a better-than-neutral score to a Likert-scale question like this: “Based on this statement, how likely are you to support candidate X?”

The measure of effectiveness would be people liking, sharing, subscribing, donating, talking about it on their social platforms, registering for events.

It would be about how many people want to be a part of what we’re building, not just approve of what we’re saying. Because we can’t wait for the election to start to build the democracy we’ll need when All This is over. We have to start now.

I mean, that’s what I’d do.

I understand that the level of opposition is more muted than the level of support, but I also don’t know what all those bubbles represent, how the issues were presented, or, you know, anything else about the sample, etc. So until they give me a dashboard log-in to let me hover over those bubbles, let’s just pretend this is a “winning” set of topics that Democrats could adopt, triangulation style. Set aside for the moment that I am generally opposed to triangulation because it too often fails to create a distinction.