Episode 7 - Vaccines for Mad Poll Disease

A couple of weeks ago, I had the opportunity to talk to Mike Podhorzer, Democratic strategist. We had a wide-ranging conversation about the state of modern polling. I want you to do two things: listen to the interview, and subscribe to his Substack (and read some of the posts I'll link to below). Here's a Spotify link to the episode (I'll put the Apple Podcasts link down below, as well):

The Big Takeaway: "I think that if the question is how to improve public polling, it'd be almost like 'don't do it.'"

We've talked about a lot of the more technical challenges of polling elsewhere, with special emphasis resting on sample methods (voter file, convenience sample, probability panels), survey modes (online v phone v text-to-mobile), and margins of error.

But there are deeper challenges facing election polling in the public sphere.

Challenge #1: Purpose

What is the poll for, really? Most public polling, conducted by news outlets in partnership with universities or polling firms, serves two purposes: predicting the outcome of the election, and generating data for news stories. We'll talk more about that in a forthcoming episode with Aaron Zitner of the Wall Street Journal. While everyone I talk to about political polling wants to understand how voters feel about things, and why they feel that way, there are limits on their ability to do this effectively.

One limitation is budget: surveys that require complex analysis are simply more expensive to conduct. The expense isn't in the sample, necessarily, it's in the analysis itself. You need experts to do that analysis, and unfortunately every public polling institution or partnership can't afford that kind of analysis.

Another limitation is respondent fatigue: if you tried to unpack a respondent's survey answers with follow-up question, complex skip logic, or open-ends, you'd not only incur the expense of analysis of those questions, you'd also risk increasing the rate of incompletes because people simply get tired or answering.

Even if you genuinely want to understand voters, there are some limitations on how much you can stretch a research dollar. A lot of public pollsters already stretch it pretty far – but put their emphasis on predictors and standardized diagnostics.

Challenge #2: Mental Models - National v. State by State

The greatest error made by national polling is, in a sense, that they are conducted at all. The United States does not, in fact, hold a national vote.

The truth is, about 10,000 state and local agencies run the elections that makeup our national election. We do not hold a national popular vote for anything. As you likely know, the President is elected by a vote of the Electoral College. The popular vote in each state provides the basis for how electors behave; but the United States Constitution does not offer any of its citizens an affirmative voting right.

So why do we poll like that's how it works? Why not, given the budget constraints, conduct fewer polls farther apart in time, and only in the states where there is a true contest? Your list of states would be limited to the following:

Nevada (+2.5 Biden in 2020)

Arizona (+0.4 Biden in 2020)

Wisconsin (+0.6 Biden in 2020)

Michigan (+3 Biden in 2020)

Pennsylvania (+1 Biden in 2020)

Georgia (+0.3 Biden in 2020)

North Carolina (+1 Trump in 2020)

Those seven states represent 94 Electoral College votes that could, in theory, go either way.

This is why swing state polling gives people so much agita. WSJ had Trump leading outside their published margin of error in 2 states – Arizona and North Carolina. Now, these results are quite different from the 2020 final tallies.

Meanwhile, the New York Times swing state poll showed Trump leading outside their reported margin in 4 of the 6 states they polled. Again, these results are very far from the 2020 results: Trump lost Pennsylvania by 1pt, the NYT has him leading by 3pts; Trump lost Arizona by 0.4pts, but is polling ahead 7pts; he lost Michigan by 3pts but is up 7pts; he lost Georgia by 0.3pts, but is up 10pts; and he lost Nevada by 2.5pts, but is up 12pts.

You might look at this and think, but state-by-state polling is supposed to be "better". But here's the thing: it's actually quite a bit harder to do state-by-state polling. It's more expensive, for one thing.

These swing state polls represent upwards of 4000 respondents. The typical national poll hovers around 1500 respondents. You get state-level base sizes of about 400-600 people in a lot of swing state polling; WSJ polled 600 in each of the states they polled; NYT polled 600-1000 in the states they polled. Small base sizes generally have larger margins of error; but there are other kinds of error that can have an outsize impact on sample error, like non-response bias, or biases introduced by weighting, or even question order/design that doesn't perfectly translate state to state.

I have no idea how "wrong" or "right" these polls are, but we can compare them to each other to at least illustrate how much variation in polling there can be. Remember: these polls were conducted in almost all the same states (NYT did not poll South Carolina), with about the same total sample size, about a month apart.

Let's look at the top line number, sans MoE for each of these polls and illustrate the differences.

I think if you want to know why people freaked out way more about the NYT poll than the WSJ poll, it's probably because the NYT had some more extreme top line numbers. But both polls tend to be pretty wide of the results in 2020.

If the WSJ's more conservative take is your preference, the comparison to the 2020 election either shows large polling errors or dramatic swings in voter preference.

It's certainly possible, but it's not likely, that these results will turn out to be the final results. And that's fine – because they are, as everyone who's ever conducted a survey likes to say, snapshots in time.

Challenge #3: Mental Models: Voters Taking Surveys

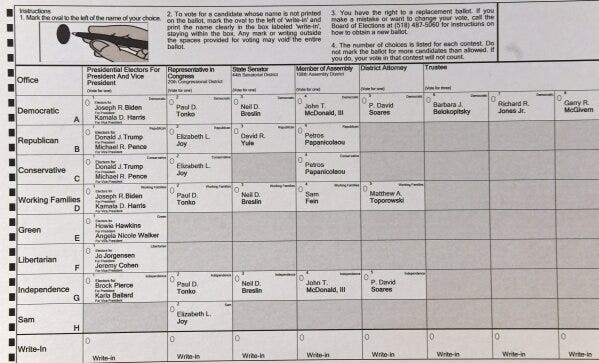

But what are they snapshots of? What do voters think they are doing when they answer a poll? Being asked a question online or on the phone like, "If the 2024 presidential election were held today, who would you vote for if the candidates were Joe Biden and Donald Trump?" is not the same as what you see on a ballot. Here's what you might have seen if you voted in New York in 2020:

Whatever you think of this design, it isn't like answering the survey question about candidate preference.

There's another way voting in a polling booth and answering a poll are not alike: People know they're not the same thing. There's literally no way to design around this kind of problem. The day I answer a poll is generally not the day I actually vote; I do not know the things I will know come November; I do not feel today about the election or the candidates the way I will feel in November; the stakes are completely different; my sense of moral or civic accountability is completely different. These are not the same activities.

So what do we do?

The more I talk to political scientists and political psychologists, to pollsters and strategists and journalists, the more I feel that there are too many things done in the universe of political polling "because tradition". The question types and diagnostic batteries are under-theorized and potentially out of date. The issue statements are overly broad with limited opportunity for follow-up (when I select "economY" and you select "economy" are we talking about the same things?). The question types don't match the way the results are reported. For example, a question that asks people to rank their top 3 issues, or to select their top issue does not tell you anything about the intensity of their feelings about that issue, and it also doesn't tell you anything about the salience of the issue as a motivator to vote at all, and for one candidate or party over another.

I'm going to keep digging in on this idea of salience – I think if you want to understand what drives people to any kind of action, in politics or in marketing, salience is the metric that matters most. But for now, do give my conversation with Mike a listen and check out some of the links below:

Cross Tabs: 7: Vaccines for Mad Poll Disease, with Michael Podhorzer on Apple Podcasts

Mentioned Articles

"A Cure for Mad Poll Disease" (Weekend Reading)

"Mad Poll Disease Redux" (Weekend Reading)

"We Gave Four Good Pollsters the Same Raw Data. They Had Four Different Results." (The New York Times)

"Sweeping Raids, Giant Camps and Mass Deportations: Inside Trump's 2025 Immigration Plans" (The New York Times)

"The Two Nations of America" (Weekend Reading)

Our Guest

Michael Podhorzer is the former political director of the AFL-CIO. He founded the Analyst Institute, the Independent Strategic Research Collaborative (ISRC), the Defend Democracy Project, and the Polling Consortium. He helped found America Votes, Working America, For Our Future, and Catalist.

In 2020, Podhorzer played a pivotal organizing role in the effort to prevent Trump from overturning the election results, and his early leadership in evidence-driven politics was documented in the 2013 book The Victory Lab.

He is now a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress.

Catalist: A national voter file for progressives and labor that Mike Podhorzer was instrumental in improving understanding of political trends.

The Analyst Institute: Dedicated to understanding what works and what doesn't in political campaigns, an organization Mike Podhorzer was involved in starting.

The Research Collaborative: Focuses on how people understand and process the rise of fascism and threats to democracy, an organization Mike Podhorzer was involved in starting.

Defend Democracy Project: Provides strategic communication and works with the media on issues related to defending democracy, an organization Mike Podhorzer helped start.

Weekend Reading: Mike Podhorzer's Substack, where he writes about political issues, polling, and strategically using data in campaigns.

And don't forget to subscribe to Cross Tabs in your favorite podcast app: